Alaska’s Aleutian Islands curve south and then west eleven hundred miles into the North Pacific. The islands at the end of this string lie perilously close to Japan. Strategically, the islands offered the Japanese fifteen thousand miles of undefended U.S. coastline with no overland transport route between the lower 48 states and the Alaska Territory for access.

To the War Department the overland road into the Alaska Territory was now a strategic imperative in the face of a feared imminent attack by the Japanese.

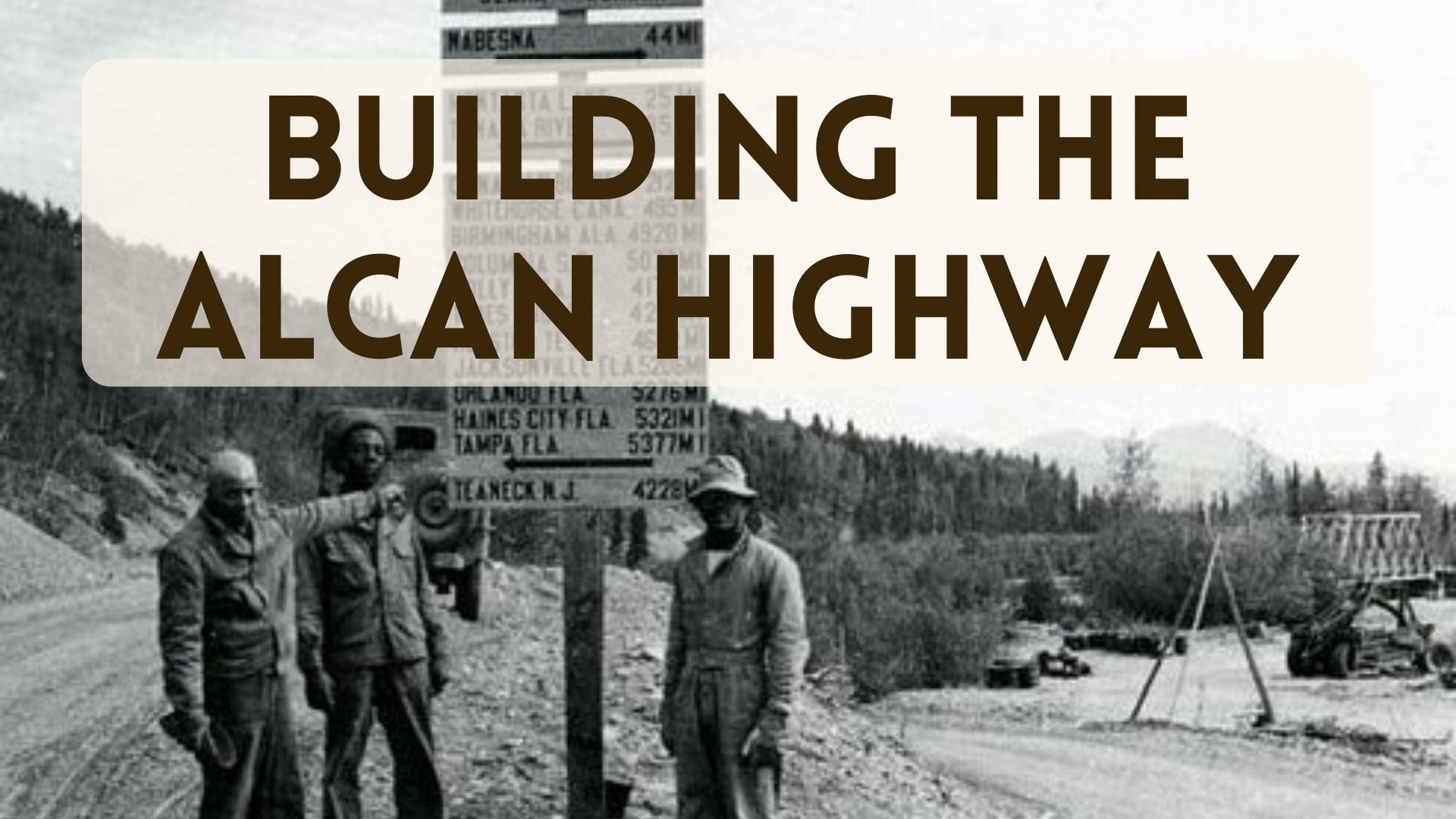

The Alaska-Canada Highway (AlCan) was a construction project likened in scale to “building the Panama Canal.” The Army Corps of Engineers planned to build 1,600 miles of Alaska Highway through the rugged and remote subarctic north of Canada and Alaska in eight months. They originally planned to use four white regiments–the 35th, the 340th, the 341st, and the 18th.

When the Colonel in charge flew over the frozen ground, frozen rivers, and snow-covered mountains he realized he would need more units. The Corps’ white engineering regiments had been dispatched to the Pacific theater, so they reluctantly added three segregated Black regiments to the lineup—The 93rd, the 95th, and the 97th. Altogether about 11,000 soldiers, about a third of them Black, worked through the spring, summer and fall of 1942 to build the original Alaska-Canadian (ALCAN) Highway.

The Army was still segregated; Black units were led by white officers who were usually Southerners who supposedly “understood” blacks but in fact disparaged them. As late as 1936, a manpower assessment from the Army War College described Black soldiers as shiftless, dishonest, and lazy. It was a view shared by the Army in general.

Senior commanders of the road-building effort, one of them the son of a Confederate general, declared that Blacks (often called something else) might be able to wield picks and shovels, but not the heavy equipment the job required.

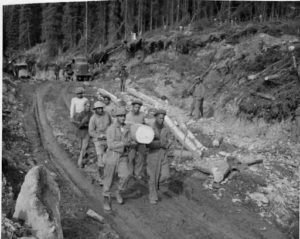

Seasoned and experienced Black troops who had been building roads for a year, many who had attended Diesel Mechanic School, arrived with their own heavy equipment only to have it redistributed to less experienced white units. The Black units were issued hand tools, picks, shovels axes and hand saws. Any heavy equipment they sometimes received were the vehicles otherwise headed for the scrapheap. And sometimes they lost even that to white units whose equipment was delayed or damaged.

Like everyone else, the black soldiers faced extreme conditions. Moving every three days, they worked 7 days a week, 16 hours a day. First, they endured mosquitoes, black flies, heat, muskeg (peat bogs), melting permafrost, and mud in Summer, then glacial ice, snow, and sub-zero temperatures in Winter. But the Black troops also had to contend with relentless racism and inferior supplies, sleeping in canvas tents in weather 40 to 60 degrees below zero while white soldiers had Quonset huts.

The Corps of Engineers had gone to great lengths to hide the three Black units. The Black soldiers were not permitted to mix with local Canadians. Their assignments were chosen to keep them away from any settlements large or small. Since the farther away from base camp you were, the harder the living conditions, there was an added burden on the Black troops.

Film crews, journalists, and photographers in 1942 followed the white regiments and ignored the black men who remained ghosts in history.

The hard work, resolve to survive, and determination to prove the Army wrong changed some attitudes toward these Black engineering units. When interviewed in 1992, Colonel Heath Twichell admitted that he was ‘heartsick’ when given command of a 95th Black regiment, he thought his chances of promotion were gone. When he took command, his troops had a serious moral problem due to the racism of the previous leader. Twichell realized his troops needed to rise to a challenge.

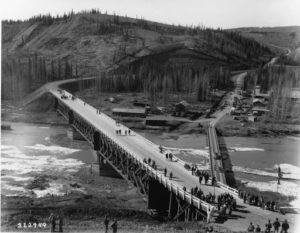

The Sikanni Chief River in the mountains of British Columbia, presented that challenge in a big way. Army Engineers at desks far away estimated two weeks to bridge the river.

Twichell convinced Colonel O’Connor, Southern Sector Commander, that the 95th could build the trestle bridge across the Sikanni Chief River, a 300-foot-wide cold glacial river with a running current of ten miles an hour. O’Connor wanted the bridge built in one week. And he reluctantly agreed to give the 95th a shot at building it.

Twichell brought his Company A, 166 men, to the site; their mission to build a trestle bridge across in just five days. Company A surprised the Colonel by promptly raising the ante. Every man agreed to bet a month’s pay that they could do it in four days. Unknown until now, the 95th got the attention of the rumor mill. Word of the bet spread the length of the highway.

Twichell later described it as “72 hours of ceaseless effort,” at times by the light of their truck headlights, the men felled trees, squared timbers, assembled trestles, and waded chest deep into the ice-cold river to float them into position. They cut and assembled wood to form the bridge’s decking and built and installed heavy timber cribs to protect its footings from ice and driftwood. Wading, and working in the glacial water, they took shifts to warm and thaw out before returning to the effort. The bridge was completed in an historic 84 hours.

Other Black units created their own challenges, they ‘borrowed’ heavy equipment from white units to complete sections of the road during the night to show what they could do.

Twichell wrote home, “We hear less and less about the supposed deficiencies of Negro troops.” And that son of a Confederate General ordered confederate flags removed.

On October 24, 1942, the 97th Black and 18th all-white regiments met head-on in the spruce forests at Beaver Creek in the Yukon Territory version of ‘’driving the golden spike’ as the north and south sections joined to complete the road in eight months and twelve days.

Six years later, President Harry S. Truman ordered the Army desegregated, and many historians cite the Alcan experience and the Tuskegee Airmen as helping make that possible.

The Alaska Highway opened to the public in 1948. The highway was named an International Historical Engineering Landmark in 1996.

Two soldiers from Poolesville were members of the Black regiments involved in the building of the AlCan Highway. Leroy Alger Palmer, born in Poolesville in 1916 and buried at Arlington Cemetery listed his Aunt Buelah May Terry as family. Phillip Samuel Johnson III, born in 1919 and known as the mayor of Sugarland, was the uncle of Gwen Hebron Reese. He was a member of the 95th Black Engineer Regiment.

Fifty years after the completion of the highway, the essential role played by black troops in Alaska Highway construction was celebrated on June 14th, 1993, when the ALCAN veterans were honored at the Pentagon in Washington, D.C.