Before the late 1930s, most US pilots got their training in the military, which was segregated. The only Black pilots were civilians who were either self-taught, learned to fly in Black flying clubs, or overseas.

In 1938, in anticipation of WW II, the Civilian Pilot Training Program (CPTP) was initiated with federal funds to train increasing numbers of civilian pilots. The purpose of the CPTP was to provide introductory aviation training to thousands of college students. It was essentially a screening program for military pilot training. Beginning with ‘ground school” training at nine white colleges and universities, both men and women learned to fly.

In 1941, under pressure from Black pilots and civil rights groups, and facing an ever-growing need for trained pilots, President Franklin D. Roosevelt directed the Army Air Corps to accept Black Americans into this civilian pilot training. The CPTP included an antidiscrimination rule – a landmark in racial equality for Blacks in aviation. The training remained segregated.

Instruction for Black students began at six historically Black colleges: the West Virginia State College for Negroes, Howard University in Washington, D.C., Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, Hampton Institute in Virginia, Delaware State College for Colored Students, and North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College.

The CPTP trained 300 Black pilots by 1941. The Black graduates of the CPTP could not continue their flight training. The men could not join the military to complete their training, since there were no African American units in the segregated Army Air Corps, and they were barred from joining any existing units which were all White.

The White graduates of the program could apply for further training. The men could volunteer for military flying units and the women applied to the Womens Airforce Service Pilots (WASPS), a civilian flying corps who ferried planes and towed shooting targets.

African American women graduates were barred from further training in the WASPS while several Native American and Chinese American women of color were permitted to join.

In 1941, the NAACP sued the War Department on behalf of a Howard University-trained pilot to secure the promised military training that Black CPTP graduates had been denied. Soon afterwards, the Air Corps created the 99th fighter squadron for African Americans.

Because it was a segregated unit, supporting personnel who were Black bombardiers, navigators, gunnery crews, mechanics, and instructors also had to be trained. They too are considered Tuskegee Airmen who kept the pilots aloft.

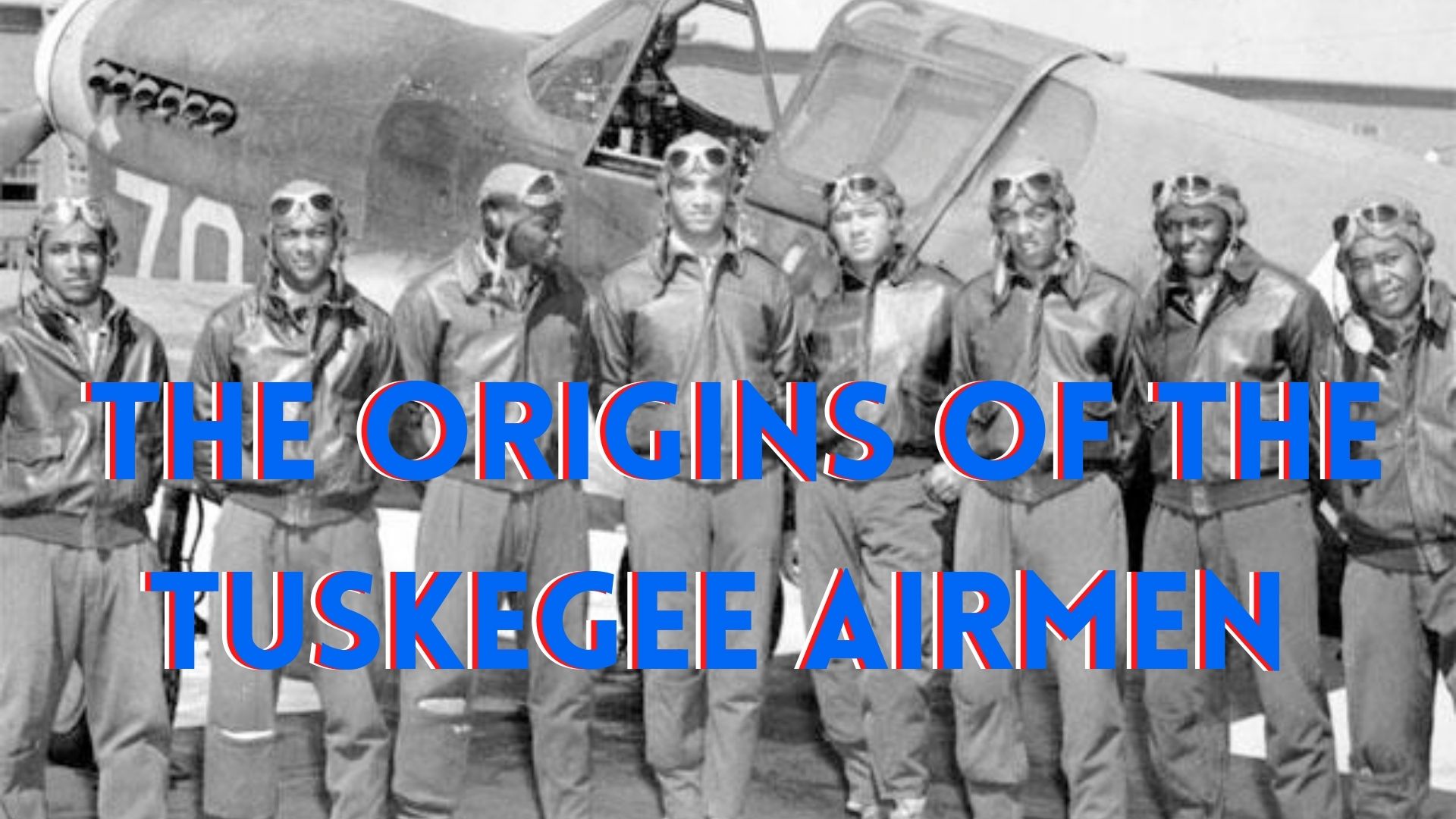

The military selected the Tuskegee Institute to train these Black military pilots because of its commitment to aeronautical training. Tuskegee had the facilities, and engineering and technical instructors, as well as a climate for year-round flying. The Tuskegee civilian program was expanded to become the center for Black American Military aviation during World War II.

Although the orders for this change were probably already in process, Eleanor Roosevelt, who was attending a Rosenwald Fund meeting at the Tuskegee Institute, had her photo taken after a flight with civilian flight instructor, C. Alfred “Chief” Anderson. The photo was printed in the media, publicizing Black pilots, and was credited with influencing FDR to open the military to Black pilots.

Tuskegee Army Air Field (TAAF) became the only Army installation performing all three phases of pilot training (basic, advanced, and transition) at a single location. The first TAAF aviation cadet class completed training in March 1942. Called the “Tuskegee Experience” by Tuskegee alumni, the program was originally called the “Tuskegee Experiment,” and was conducted by the U.S. War Department and the Army Air Corps from 1941-1949. Some in the military thought the experiment would prove a government report that Black men lacked intelligence, skill, courage and patriotism to fly.

Throughout their training at Tuskegee, no training standards were lowered for pilots or any of the others in the fields of meteorology, intelligence, engineering, medicine, and other support positions. From 1941 to 1946, approximately 1,000 pilots graduated from TAAF, receiving their commissions and pilot wings.

They overcame segregation and prejudice to become one of the most highly respected fighter groups of World War II. They proved conclusively that Black Americans could fly and maintain sophisticated combat aircraft.

The Black airmen who became single-engine or multi-engine pilots were trained at Tuskegee Army Air Field (TAAF). The 99th’s first combat mission was to attack the small strategic volcanic island of Pantelleria, in the Mediterranean Sea to clear the sea lanes for the Allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943.

Bomber crews named the Tuskegee Airmen “Red-Tail Angels” after the red tail markings on their aircraft. Also known as “Black” or “Lonely Eagles,” the German Luftwaffe called them “Black Bird Men.” The Tuskegee Airmen flew in the Mediterranean theater of operations.

The Airmen completed 15,500 missions in Europe and North Africa, destroyed over 260 enemy aircraft, sank one enemy destroyer, and demolished numerous enemy installations. Several aviators died in combat. The Tuskegee Airmen were awarded numerous high honors, including Distinguished Flying Crosses, Legions of Merit, Silver Stars, Purple Hearts, the Croix de Guerre, and the Red Star of Yugoslavia.

Their impressive performance earned them more than 150 Distinguished Flying Crosses and helped encourage the eventual integration of the U.S. armed forces.

The Tuskegee Airmen’s achievements, together with the men and women who supported them, paved the way for full integration of the U.S. military.

The CPTP/WTS program was largely phased out in the summer of 1944, but not before 435,165 people, including hundreds of women and African Americans, had been taught to fly. Notable legends trained under the CPTP include Astronaut/Senator John Glenn, and former Senator George McGovern,

After segregation in the military was ended in 1948 by President Harry S. Truman’s Executive Order 9981, the veteran Tuskegee Airmen now found themselves in high demand throughout the newly formed United States Air Force. Some taught in civilian flight schools, such as the Black-owned Columbia Air Center in Maryland. On 11 May 1949, Air Force Letter 35.3 was published, which mandated that Black Airmen be screened for reassignment to formerly all-White units according to qualifications.