In the seventeenth century, the slave states passed laws declaring that the children of an enslaved mother inherited her legal status. Eventually the children born of any free person and an enslaved person were also declared slaves.

Mary and Emily Edmonson were two of fourteen children. Their father, Paul Edmonson, was a black man from Madagascar who was freed in his owner’s will. Their mother, Amelia (Milly) Culver was an enslaved woman in the Berry District of Montgomery County, Maryland. Paul Edmonson purchased land in Norbeck where his enslaved wife was permitted to live with him and work for her master. Four of the older Edmonson sisters bought their freedom with the help of their family and husbands.

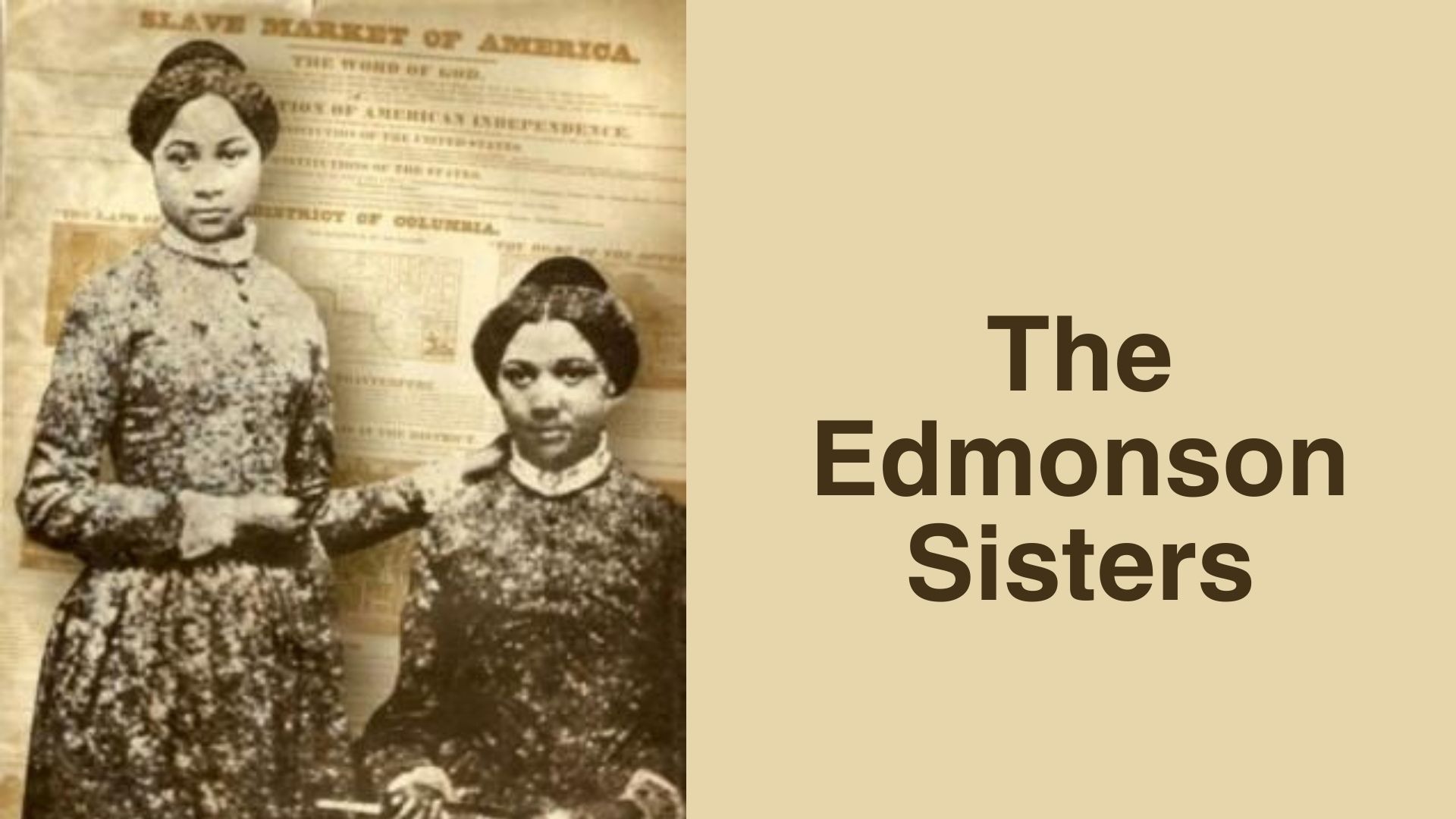

The master would not allow the four older brothers and the younger siblings to buy their freedom. Two of the younger Edmonson sisters, Mary and Emily, age 15 and 13, were described as “two respectable young women of light complexion”. They were hired out by their mistress to work as servants in two “better” private homes in Washington, D.C. The brothers were also “hired out” in DC. Under the lease agreement their wages were paid to their mistress. These remaining Edmonson siblings were refused the opportunity to buy their freedom because their owners did not want to lose the income they generated. In the late 1840s the sisters would become icons in the abolitionist movement.

Daniel Bell, a formerly enslaved Navy Yard blacksmith was frightened that the widow of his former master was about to sell off Bell’s wife, Mary, six of his children and two grandchildren. For 15 years, the Bell family had been suing in court to have the widow abide by the writ of manumission signed by her husband before he died.

On April 15, 1848, Bell and Samuel Edmonson planned the escape of their families. The Edmonson siblings, Mary, Emily, and their four older brothers, Samuel, Richard, Ephraim, and John departed from a Washington, D.C. wharf on a sixty-five-foot Chesapeake Bay schooner, The Pearl.

Word spread through the enslaved community and the Pearl set sail with 77 escapees, not just the Bell and Edmonson families. It was the largest non-violent escape of runaways in U.S. history. They belonged to “41 of the most prominent families in Washington and Georgetown and were valued at $100,000.”

Stormy weather kept the ship stalled overnight at Point Lookout, the southern mouth of the Chesapeake. At dawn, multiple slaveholders discovered their “property” missing and sent 35 armed men by steamboat to recapture the escapees. The posse overtook the Pearl, locked the crew and passengers in the hold, and towed the ship back to Washington, D.C. The Pearl was met by a violent pro slavery mob which rioted for three days and threatened Washington abolitionists, the runaways, and the Pearl’s crew.

The six Edmonson siblings were purchased by the Alexandria slave dealer Joseph Bruin. Bruin used his property at 1707 Duke Street as a slave jail where he held Blacks before selling them, primarily to slaveholders in the Deep South.

All 77 runaways were sold to slave trader partners Bruin & Hill in Alexandria. They were sent South on the Brig Union to be sold in Georgia and New Orleans. The Edmonson sisters, just 15 and 13 were displayed in New Orleans on an open porch facing the street hoping to attract buyers for high-priced “fancy girls”.

While they were held in New Orleans, the Edmonsons met a freed cooper who was their older brother, Hamilton. A yellow fever epidemic struck New Orleans and forced Bruin & Hill to send the two light-skinned Edmonson girls back to Alexandria, Virginia, to protect their investment. The girls worked as laundresses while in captivity waiting for their return to New Orleans.

Since the escape attempt, the girl’s father Paul, had been trying to raise the $2,250 to buy Mary and Emily’s freedom. He traveled north where he met the Reverend Henry Ward Beecher whose Plymouth Church members helped to raise the ’ransom’ before the girls returned to New Orleans. The sisters were emancipated on November 4, 1848.

Henry Ward Beecher and his sister Harriet Beecher Stowe continued to support the sisters financially when they enrolled in the interracial New York Central College and Oberlin College in Ohio. The girls became part of the abolitionist movement, appearing with Frederick Douglas at the 1850 Slave Law Convention in Cazenovia, New York to protest the Fugitive Slave Act. The Pearl incident was influential in the passing of the Compromise of 1850, which outlawed the slave trade but not slavery in the District of Columbia and strengthened the Fugitive Slave Laws.

The Edmonson’s older brother Hamilton and their father arranged for Samuel Edmonson’s sale to an Englishman as a butler and later bought the freedom of Ephraim and John Edmonson. Samuel Edmonson never abandoned his pursuit of freedom. In 1859 he escaped on a ship to Jamaica. From there he went on to Liverpool and, with his wife and child, sailed to a new life in Australia.

Mary Edmonson died of tuberculosis while at school in Ohio. Emily Edmonson returned to Washington, DC to Myrtilla Minor’s Normal School for Colored Girls, a teachers’ college.

Emily married Larkin Johnson and moved to Sandy Spring, MD. She continued her abolitionist activism and became a founder of the Hillsdale community of Anacostia in DC. Emily Johnson died on September 15, 1895, at her home on Howard Road in Hillsdale shortly after the death of her longtime friend and Hillsdale neighbor, Frederick Douglas.

Harriet Beecher Stowe included part of the Edmonson sisters’ history, the Pearl Incident, and other factual accounts of slavery in her book A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1853). It was published to document the veracity of her depiction of slavery in her anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852).

The Edmonson sisters are memorialized in a 10-foot bronze statue of the two inspiring 19th Century Black women, which stands in front of a 21st Century office building at 1701 Duke Street in Alexandria, VA, near the former location of the Bruin & Hill Slave Traders where the Pearl escapees were imprisoned.