Julius Rosenwald was the son of Jewish German immigrants. He was born in 1862 in Springfield, IL, and lived just a block from Abraham Lincoln’s family home. His uncle Julius Hammerslough was at Lincoln’s inauguration and accompanied Lincoln’s body back to Springfield after his assassination. Rosenwald’s parents were successful clothing merchants who supplied Union uniforms during the Civil War.

Sears, Roebuck & Co. was one of his clients. In 1895, he became a partner in Sears, eventually becoming its president and CEO. Rosenwald’s vision and business savvy helped transform Sears from a struggling enterprise into a powerhouse national retailer and made him richer than his wildest dreams.

According to the Sears website, the annual sales at Sears skyrocketed from $750,000 in 1895 to $40 million in 1907. Rosenwald was one of the richest men in America. His rabbi, Emil Hirsch, a nationally known promoter of faith-based social activism, helped to guide Rosenwald’s philanthropy.

It started within the Jewish community — funding schools and hospitals. Rosenwald played a leading role in many progressive social reform organizations in Chicago and became the first president of the combined Jewish Charities of Chicago. He contributed $6 million to support Russian Jews fleeing the Russian Revolution. He established one of the first urban housing projects on Chicago’s South Side, and he founded and single-handedly financed the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago.

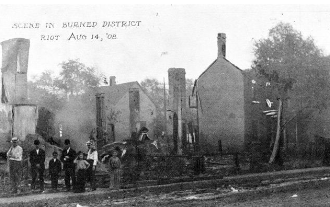

In 1908, a shocking 3-day race riot in the hometown of Lincoln and Rosenwald, was a painful example of the treatment of African Americans in the United States. From 5,000 to 10,000 whites rampaged through the “black belt” of town looting Black businesses, killing Black residents, and setting fires. It had a profound effect on Rosenwald’s philanthropy. When he met Booker T. Washington in 1910, Rosenwald became a Trustee of the Tuskegee Institute.

In 1908, a shocking 3-day race riot in the hometown of Lincoln and Rosenwald, was a painful example of the treatment of African Americans in the United States. From 5,000 to 10,000 whites rampaged through the “black belt” of town looting Black businesses, killing Black residents, and setting fires. It had a profound effect on Rosenwald’s philanthropy. When he met Booker T. Washington in 1910, Rosenwald became a Trustee of the Tuskegee Institute.

In 1912, on Rosenwald’s fiftieth birthday, he gave a grant to Booker T. Washington’s Tuskegee Institute to build six African American schools in Alabama as a pilot project. Rosenwald continued to provide money to the institute, and more schools were built. The schools had standardized plans developed by Tuskegee architect Robert R. Taylor with assistance from William A. Hazel, and George Washington Carver at the Tuskegee Institute. During the school-building program, the design and orientation of the schools improved lighting, ventilation, and sanitation for Black schools in Southern states.

When Booker T. Washington died in 1915, Rosenwald managed the building fund without the Tuskegee Institute and turned it into an independent foundation. In 1917 he created the Rosenwald Fund for the “well-being of mankind”. Through matching grants, over 5,300 schools were built for African American children in 15 Southern States.

Philanthropy Roundtable noted that, at the time of his death in 1932, the schools Rosenwald built were educating 35 percent of all Black students in the American South, and 27 percent of all Black American children attended a Rosenwald-funded public school.

Using his matching grant model, Rosenwald also built twenty-four YMCA and two YWCA community centers in cities throughout the country, and urban dormitories for blacks during the segregated era. He funded one-third of the litigation costs of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case.

Rosenwald Fund grants required community buy-in, a dollar-for-dollar match. Rosenwald aided African Americans seeking higher education with scholarships for artists, scientists, and intellectuals. Writer Ralph Ellison, singer Marian Anderson, diplomat and future Nobel Peace Prize winner Ralph Bunche, author James Baldwin, historian John Hope Franklin, and psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Phipps Clark were among the many people who benefited from a Rosenwald-endowed scholarship. The scholarship fund continued until 1948, awarding 588 fellowships to African Americans and 222 to “white Southerners.

In one of his speeches, Rosenwald said, ‘We like to look down on the Russians because of the way they treat the Jews, and yet we turn around, and the way we treat our African Americans is not much better”.

Rosenwald contributed to many Jewish causes. He was the largest single donor to the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee’s 1917 campaign to help European victims of pogroms and other violence during World War I. He traveled throughout the country encouraging others to donate. In 1929, he pledged $500,000 to the Hebrew Union College endowment fund contingent upon $4,000,000 being raised in six months. Before he died in 1932, Rosenwald donated more than one billion dollars (in today’s money).

Maryland has no comprehensive survey of Rosenwald sites. The Maryland Historic Trust reports 156 schools in Maryland, while Sherri Marsh, professional architectural researcher in Ann Arundel County, reports that the Rosenwald files at Fisk University cite 292 schools in Maryland.

In the Poolesville community of Jerusalem, we have our own Rosenwald school that was built in 1926. Join Historic Medley on March 15 to hear more about schools for Black students in pre-integration Western Montgomery County.

In 2002 the National Trust for Historic Preservation listed Rosenwald Schools on its 11 Most Endangered Historic Places list and called the program “the most important initiative to advance black education in the early 20th century.”