The second Tuesday in October is Ada Lovelace Day, which honors an extraordinary mathematician, and celebrates women in STEM. You may have seen the movie “The Imitation Game” about Alan Turing and his Enigma machine which turned the tide of WWII by deciphering coded messages. Turing’s creation was inspired by the 100-year-old writings of mathematician Ada Lovelace.

Augusta Ada Byron was the daughter of the poet Lord Byron and was brought up by her mother, Annabella, after he passed. Her mother feared that she would inherit her father’s poetic temperament, and gave Ada a strict upbringing of logic, science, and mathematics. Ada, born in 1815, became fascinated with mechanisms and designed steam flying machines, poring over the scientific magazines of the time and embracing the British Industrial revolution.

At 17, she met mathematician Charles Babbage and was fascinated by his “Difference Machine” a precursor of the calculator. He became Ada’s mentor and helped her study advanced mathematics with a professor at the University of London. She helped Babbage develop a device called The Analytical Engine; an early predecessor of the modern computer.

She married William King-Noel, 1st Earl of Lovelace on 8 July 1835, becoming Lady King, Countess of Lovelace. They had three children.

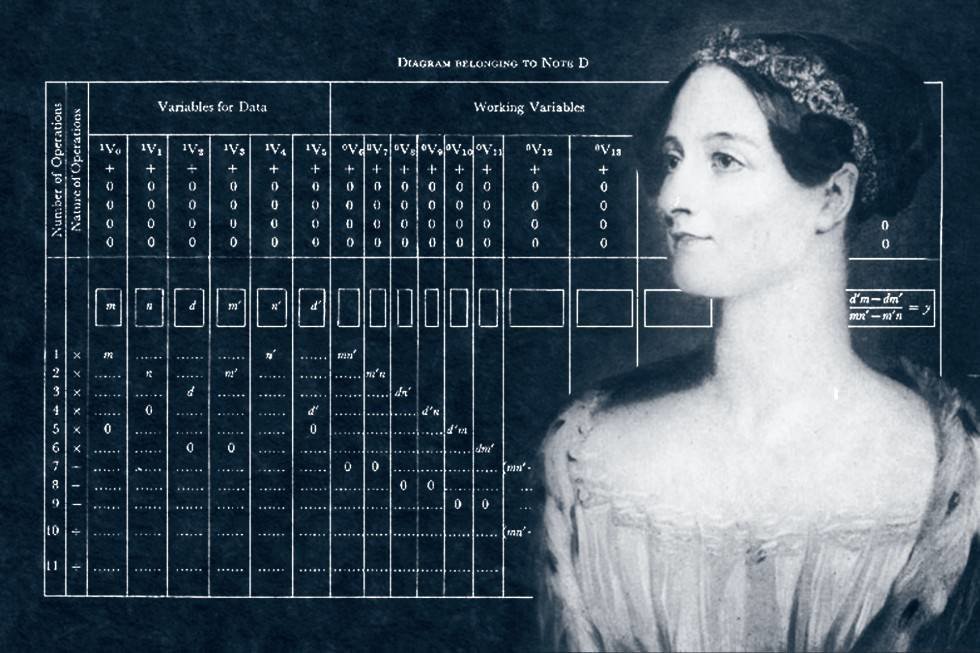

In 1842, Babbage asked Ada to translate another mathematician’s article about his Analytical Engine from French. She not only translated the text into English, but added copious annotations, including her own thoughts and ideas about the machine. In these notes, which were three times as long as the original article, Lovelace described, step by step, how the machine could calculate a sequence of numbers, creating the first algorithm designed to be executed by a machine. This is an essential component of any computing device. The algorithm was designed to compute Bernoulli numbers, which have many applications in science and engineering. In 1943, Her translation and notes were published in their entirety by R. & J. E. Taylor as “Sketch of the Analytical Engine, with Notes from the Translator” under the initials A.A.L. She was not revealed as the author until six years later.

Lovelace’s programs for the Analytical Engine were elaborate and complete. They were the first to be published, so she is often referred to as “the first computer programmer”.

Lovelace’s article attracted little attention when she was alive. In her later years, she tried to develop mathematical schemes for winning at gambling but failed. Ada’s notes were uncovered in the 1940s by Alan Turing and inspired his work on the first modern computers in the 1940s.

In the 1950s, her notes were reintroduced to the world by B.V. Bowden, who republished them in his 1953 book Faster Than Thought: A Symposium on Digital Computing Machines. Since then, Ada has received many posthumous honors for her work.

A lot of people would say that her biggest achievement was being the first person to understand the Analytical Engine’s creative potential. She posited that the engine could do a lot more than just calculate numbers. She believed it could create art and music and had a capacity for self-awareness and, in particular, consciousness. She also believed that the computer could learn and evolve and achieve similar levels of intelligence to humans in the future, if the machine was given the correct inputs and programming.

It is remarkable that Lovelace’s observations on universal computing and artificial intelligence remain so influential today even though they were based on a fully mechanical, steam-powered machine that transmitted information through rods instead of electrical wires and was never even finished. Her writing on the Analytical Engine is an incredible work that was understood by very few of her contemporaries yet remains relevant almost two centuries later. Though John McCarthy, the Father of Artificial Intelligence, coined that phrase in 1955, surely Ada Lovelace must be the mother of AI for having recognized this potential in machines more than 100 years before.

Ada’s influence is seen in a high-level programming language, Ada, named for Ada Lovelace and written for the Department of Defense between 1977 to 1983. It superseded over 450 programming languages used by the DoD at that time. The Lovelace 2.0 Test is designed to test whether computers can originate concepts.

Ada Lovelace died of cancer in 1858 at the age of 36, a few short years after the publication of her groundbreaking concepts. Charles Babbage died 13 years later without ever completing his Analytical Engine. One must wonder how our world would have changed if this incredibly visionary mathematician, Ada Lovelace, had an extra fifty years for her work.